Challenge

Universities are not required to complete hazard mitigation plans. Most do not, instead relying on and participating in their local jurisdiction or county plan. The county hazard mitigation plan covers a broad geographic area and did not have the level of detail needed to take all the university associated risks into account.

East Tennessee State University (ETSU) is like a small city with unique risks and vulnerabilities, which are spread out among several smaller ancillary campuses in different jurisdictions. Andrew Worley, the university’s emergency management specialist, explained that “we felt that there were specific needs and concerns about a university campus that may not apply to cities and counties.” For example, the university maintains its own critical facilities, such as its emergency operations center, food services, power plant and telecommunications buildings.

Solution

ETSU decided to develop a university-specific hazard mitigation plan to address the risks and vulnerabilities that apply to their campuses. The university developed the plan in-house through the Geoinformatics and Disaster Science (GADS) Lab.

“We’re doing it all in-house because we have the resources that can do it — we have the engineering folks, we have our own public safety department,” Worley said.

FEMA provided a grant to support plan development by recruiting and hiring graduate students. The GADS Lab worked with the University Department of Public Safety to assess each campus, develop geospatial databases to serve as the basis for modeling, analysis, and interactive web map services and fly and process their own drone imagery for building assessments.

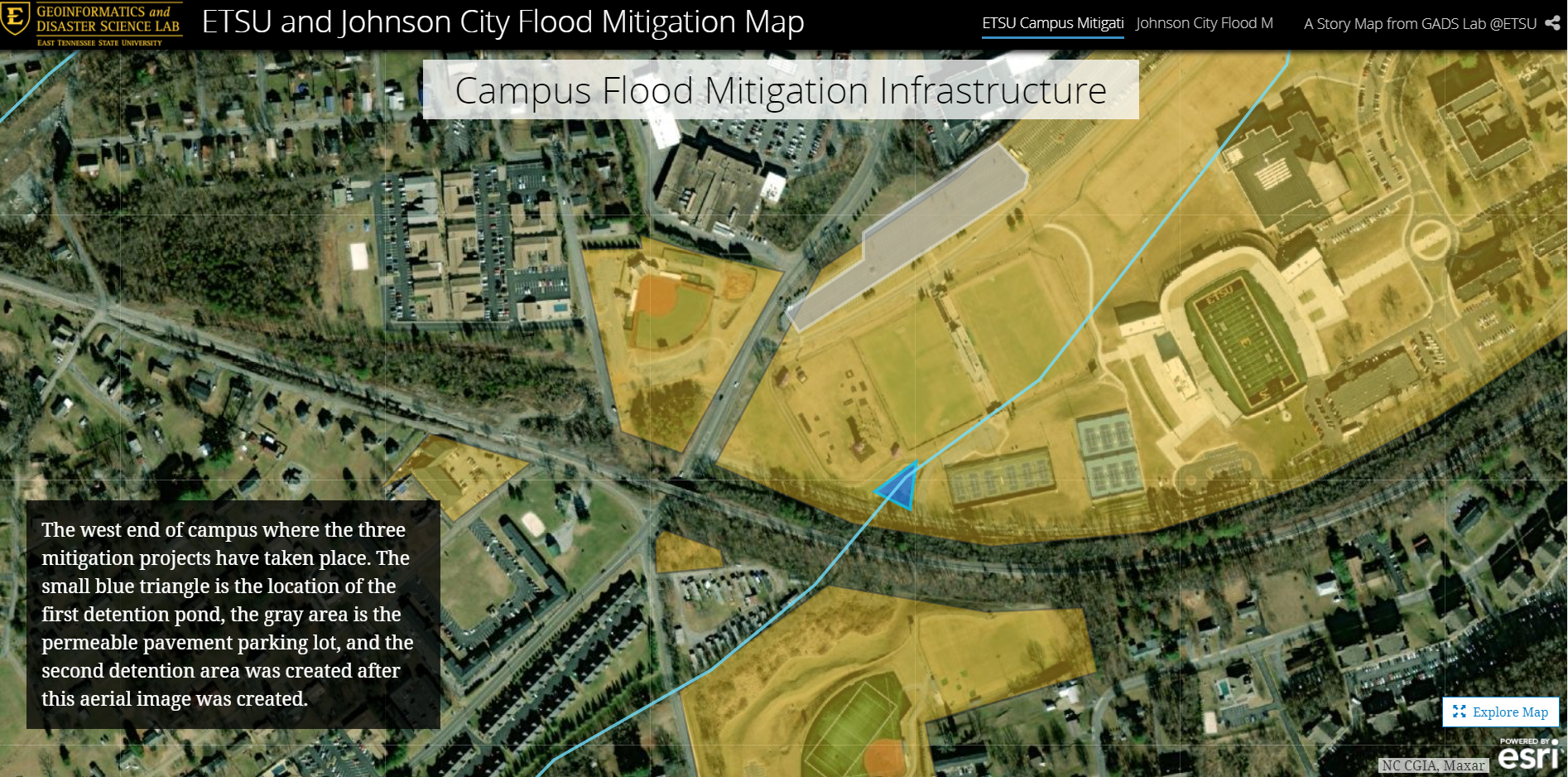

As members of the campus community, the GADS Lab is deeply connected with the university landscape. One of the essential products created by the lab during the plan development process was the ETSU GIS Open Data Hub. Risk and vulnerability assessments were not comprehensive before the data hub’s development. The GADS lab developed various useful tools, products and communication materials through the data hub including a story map for ETSU and Johnson City, Tennessee to share information on flood risks, previous flood events and current mitigation efforts.

The planning team also created a process to quantify ETSU’s unique vulnerabilities through what they called the Enhanced Priority Risk Index (EPRI). The EPRI modified the commonly used Priority Risk Index.

The EPRI includes five categories of probability used in the Priority Risk Index: impact, spatial extent, warning time and duration.added a sixth category called vulnerability. Vulnerability accounts for 25% of the score and involves a thorough, local knowledge-driven process of assessing exploitable weaknesses and countermeasures in seven sectors. These sectors include the:

- public

- responders

- continuity of operations including continued delivery of services

- property, facilities and infrastructure

- the environment

- the economic condition of the jurisdiction; and

- public confidence in the jurisdiction’s governance.

Final mitigation actions were tied to the seven sectors that may be impacted by each mitigation action. The school had state-of-the- art resources to create tools and mechanisms used to support the planning effort. For example, before this planning effort began, Computer Assisted Drafwing data and blueprints were the primary sources for infrastructure data. As part of the risk and vulnerability assessment, the planning team obtained more current digital data which the facilities team now uses to supplement the blueprints.

Key Takeaways

The mitigation plan demonstrated best practices that can be used by universities and even cities and counties in developing their hazard mitigation plans.

- Focus on Local Needs: The university prioritized building a planning process and a plan that would meet their unique needs. They made sure they researched their risks and vulnerabilities and developed mitigation actions to address those concerns.

- Get Creative with In-House Resources: The GADS Lab is part of the university. Their connections made it easier to bring stakeholders together and to communicate about risk and mitigation effectively. Using grant funds to hire student staff was a creative way to use the existing community to support mitigation.

- Mitigation Planning as a Training Opportunity: The students who worked on the plan gained real-life experience in emergency management and hazard mitigation.

- Thinking Bigger about Planning Tools: The tools used and created during the planning process are now being used in the county and region for other purposes. The maps have been an excellent community communication tool. Seeing a list of events is different than seeing it on a map.

Related Documents and Links

- East Tennessee State University Hazard Mitigation Plan

- ETSU GIS Open lData Hub

- ETSU GADS Lab

- ETSU and Johnson City Flood Mitigation Story Map

In addition, a FEMA-approved hazard mitigation plan is required for certain kinds of non-emergency disaster funding. To learn more about funding eligible projects, review the Flood Mitigation Assistance Program, Hazard Mitigation Grant Program and the new pre-disaster mitigation program, Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities.