Santa Clara Pueblo

Learning Objective: Examine how a tribal government with limited prior disaster management experience embraced a collaborative approach after a devastating fire and subsequent floods to successfully build back better.

Part One

Background

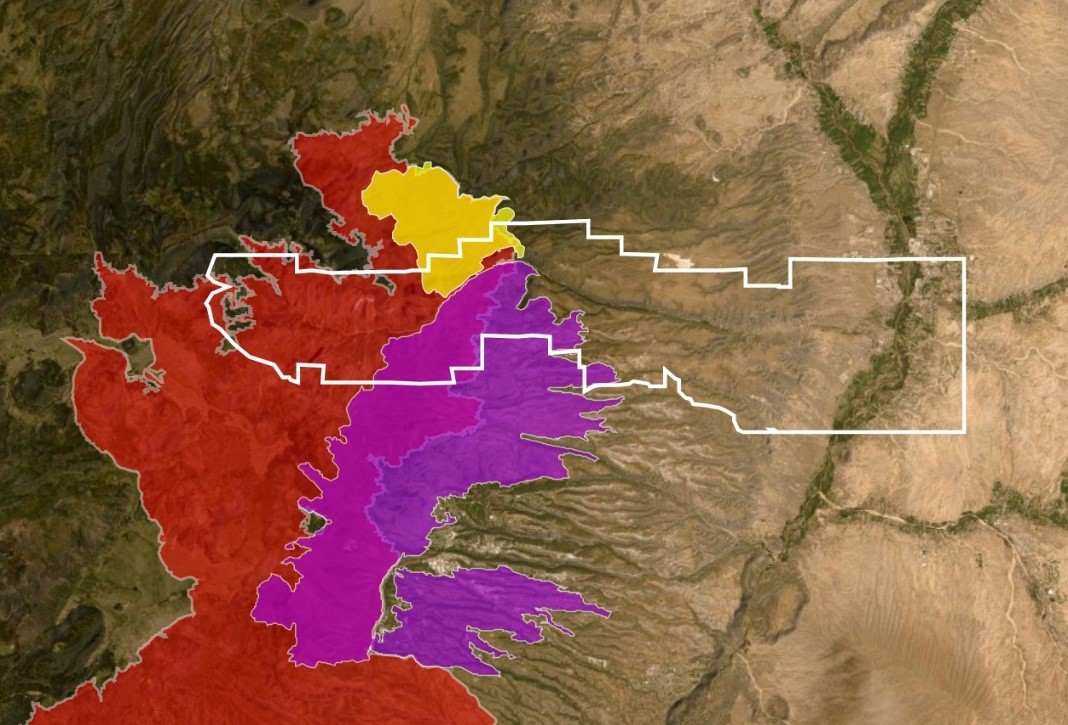

The Santa Clara Pueblo (in Tewa: Kha'p’o Owingeh) is the native homeland of Tewa-speaking Pueblo peoples. Approximately 3,500 people live on the 90 square mile pueblo, located along the Santa Clara Canyon and Creek. The 26-mile wide tribal boundary encompasses a steep elevation gradient, from an altitude of 11,000 feet in the Jemez mountains in the west to one of 5,500 feet in the Rio Grande Valley in the east.

In 2011, the Las Conchas Fire destroyed over 150,000 acres in the southwest, including the majority of the Pueblo’s forested land, which were still recovering from previous major fires. The Las Conchas Fire loosened soil in the canyon and destroyed stabilizing vegetation along its slopes, creating the perfect conditions for dangerous erosion and flash flooding in the Pueblo’s watershed - a threat realized during the 2012 – 2014 monsoon seasons.

Santa Clara Creek was rapidly inundated with debris flows carrying rocks, downed trees, and much of the canyon’s exposed soils through the heart of the Pueblo’s watershed. These flood events breached all four dams along the creek’s tributaries and severely damaged roadways, recreation sites, and cultural assets. Nearly 100 percent of the fish habitat and population was wiped out by the debris flows.

As a Federally Recognized Tribe, the Santa Clara Pueblo received federal assistance for recovery through five Presidential Disaster Declarations – three as a sub-grantee to the State of New Mexico (in 2011, 2012, and 2014), and two (both from 2013) as a direct grantee (coordinating directly with FEMA). The Pueblo became the first tribe in FEMA Region VI to receive a direct disaster declaration, and the first to implement the National Disaster Recovery Framework (NDRF) during its recovery process.

Activated Recovery Support Functions

- Community Planning and Capacity Building

- Natural and Cultural Resources

- Infrastructure Systems

The Pueblo used the NDRF as a tool to develop core recovery principles, activate Recovery Support Functions (RSFs), understand the roles and responsibilities of recovery coordinators and stakeholders, facilitate coordination, undertake pre- and post-disaster recovery planning, and capitalize opportunities to build back stronger.

Challenges

Because the wildfires so severely damaged the natural landscape along the creek’s tributaries, Santa Clara Pueblo faced a dramatic increase in flooding and erosion risk. This risk will remain elevated for many years ahead, as the forested habitat will take decades to recover. In addition to the physical damages to the community, the fires and flooding have resulted in a long-term loss of economic revenue from the tourism activities that would typically take place in the creek and canyon, a cascading effect impacting the Pueblo’s ability to recover. Finally, the situation forced the closure of sacred areas within the canyon for more than ten years (the sacred areas remain closed at the writing of this case) due to the hazards posed by charred tree limbs and soil erosion, limiting the ability of the most recent generation of tribal youth to partake in traditional and cultural activities.

The Santa Clara Pueblo faced several logistical hurdles as they began recovering after the fires and floods. The Tribal Government did not have a designated emergency management department or emergency warning system in 2011 when the Las Conchas Fire ignited, forcing first responders to communicate via radios and rely on the local news station to get the word out to residents in response to and in the immediate aftermath of the disaster. The lack of experience with Presidentially declared disasters also meant few local leaders had familiarity with FEMA workflows, project worksheets, and other administrative requirements.

Project planning was a challenge for local decision-makers due to the many competing recovery priorities. To facilitate successful and sustainable recovery projects, leaders had to prioritize recovery needs to maximize benefits, develop project plans while considering funding constraints, and determine the appropriate timing for implementation.

Santa Clara Pueblo leadership expressed particular difficulty with starting and closing out projects under the three declarations for which they were a sub-grantee to the State of New Mexico. The State had limited capacity for disaster grant close-outs, along with an extensive procurement review process, leading to delays in processing. Project management became an additional challenge for the Tribe. Delegating staff to overseeing recovery projects was difficult as staff were already obligated to their respective department duties and adopting FEMA procedures and requirements was extensive.

PART TWO

Actions

Immediately after the 2013 floods, the Pueblo started by developing an Incident Action Plan (IAP), a concise document describing objectives, priorities, and proposed strategies for the disaster response mission. The IAP is a vehicle for leadership to state their expectations and provide guidance to staff and partners managing the disaster response. Public meetings were held regularly while staff compiled the IAP, which provided a forum for community members to discuss what worked, what did not work, and lessons learned during the recovery process. The Tribal Council served as a voice for the community, with elected members representing the concerns and questions of their individual constituents at official council meetings. The staff debriefed after each engagement opportunity and funneled public comments directly into the IAP development.

Tribal leadership identified three recovery priorities:

- Community Protective Measures for Future Flood Events

- Watershed Stabilization

- Internal Capacity Building

As the community turned their attention to recovery and restoration, they embraced the principles within the National Disaster Recovery Framework (NDRF). With nearly 20,000 acres of burned forested land and many watershed, infrastructure, and cultural restoration projects to manage, the Pueblo’s administrative staff determined that the most effective recovery strategies would require expertise from several agencies, non-governmental organizations, and specialized consultants. Interagency coordination is paramount to these efforts and includes participation from the partners noted below.

Intergovernmental Partners

- Federal Emergency Management Agency

- U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

- U.S. Department of Agriculture

- Forest Service

- Natural Resources Conservation Service

- U.S. Department of the Interior

- BAER/BAR Programs

- Bureau of Indian Affairs

- Bureau of Reclamation

- Fish and Wildlife Service

- National Park Service

- U.S. Geological Survey

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency

- San Manuel Band of Mission Indians

- Shakopee Mdewakanton Tribal Nation

- State of New Mexico

The Tribe utilized planning support from the Community Planning and Capacity Building (CPCB) Recovery Support Function (RSF), led by FEMA, to develop a recovery support strategy to pursue its three recovery priorities. Tribal leadership utilized an established flood working group to leverage federal and state expertise to first identify projects that were immediately needed to protect the community, then to strategic long-term projects that would support and accelerate naturally occurring watershed restoration, working with a variety of federal and non-profit organizations to fund their objectives. The Tribe carefully weighed the long-term maintenance requirements of each project on the table and only selected those within its capacity to repair in the future.

The Santa Clara Pueblo government took a true team approach to recovery as it built out its emergency management capacity, collaborating and utilizing strengths among many departments within the Tribe. The Pueblo’s government strategically built out an entire emergency management department capable of creating scopes of work, determining period of performance, controlling cost matches, managing execution, and completing close-outs for all restoration/recovery projects.

Tribal leadership worked with the National Park Service and the U.S. Forest Service to establish Memorandums of Understanding (MOUs) for co-stewardship of 30,000 acres of forested lands adjacent to the reservation. These working relationships culminated in the establishment of the Reserved Treaty Rights Land (RTRL) Program in 2015, which utilizes authorities in the Tribal Forest Protection Act and National Indian Forest Management Act to co-manage and implement projects on federal lands surrounding Santa Clara Pueblo. These efforts help to build and strengthen a natural buffer around the canyon to mitigate the risk of erosion, runoff, and future wildfires.

The Pueblo’s recovery team also worked with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to mitigate future risks to crucial infrastructure assets along the watershed. Water runoff treatment and bridge widening projects were undertaken to manage water flows and allow for a greater volume of water to pass through during future flash flooding events in the canyon.

The Santa Clara Pueblo remained flexible as they handled each aspect of recovery, sharing resources among different recovery efforts and always keeping long-term considerations at the forefront of their decision making. To grow their capability and expertise in the face of numerous logistical challenges, staff members developed templates and internal guidance to help expedite these processes in future disasters. The Santa Clara Pueblo intentionally engaged in educational and relationship-building efforts during their recovery to help build the community’s risk awareness ahead of any future disasters. Tribal leadership ensured that pueblo residents, especially youth, contributed to restoration projects to both build internal capacity and help connect young people with the natural and cultural assets essential to the tribe’s heritage and identity.

Results

The Santa Clara Pueblo worked to build their capacity ahead of future disasters, to be prepared not just for disaster response but also for long-term recovery. The experience gained as a direct grantee under their own Presidential Disaster Declaration facilitated progress and equipped leadership and staff with the knowledge, experience, and lessons learned to be better prepared for future federal disaster procedures and requirements. The completed IAP is another tool in the Pueblo’s preparedness toolbox that can be leveraged for the next major disaster. The Pueblo continues to refine the recovery objectives and projects, using its recovery support strategy as a living document to track the status, current activities, owners, target completion date, and actual completion date of all 117 Actions identified in the recovery support strategy.

Santa Clara Forestry has shifted its efforts to a preparedness approach, working to mitigate fire risks through mechanical thinning, prescribed burns, and other fire prevention methods. These preparedness activities were funded and supported by the Bureau of Indian Affairs’ Hazardous Fuel Reduction and Resilient Landscapes programs.

The improvements made to the canyon’s bridges have allowed for higher volumes of water flow in recent flood events, with angular bridge components specifically designed to redirect water flow away from vulnerable infrastructure during emergency events. Hesco bastions, a type of gabion structure made of wire mesh and heavy fabric used to stabilize river slopes, were also installed in key locations to protect residential areas from future floodwaters. Looking forward, the Tribe is evaluating off-channel ponds as an alternative to rebuilding dams. These ponds would create water storage, recreation, and ecosystem services while concurrently serving as sediment retention basins to mitigate future flood events. These mitigation measures were supported by the US Army Corps of Engineers and serve to continue reducing the risk of inundation for the tribe’s critical facilities.

Santa Clara Pueblo believes that managing its own declaration directly is more efficient as a tribal nation than as a subrecipient through the state, citing three reasons:

- Quicker project close-outs as they can submit the close-out directly to FEMA;

- The tribe can request lower federal matching requirements as a direct recipient, if applicable under the provisions in the Stafford Act for high per capita impacts; and

- There is the ability for some of the federal funding to support some management costs, which allows the Pueblo to build internal capacity to manage disasters.

The enhanced internal capacity built through the recovery process from the 2013 floods, has led the tribe to request and receive approval to transition management of two of the open declarations from the state to the tribe. The remainder of the open projects from DR-4047 (2011) and DR-4079 (2012) are transitioning to Santa Clara Pueblo for completion and close-out.

Though tribal leadership had limited experience preparing for disasters prior to the 2011 and 2013 incidents, the Santa Clara Pueblo’s proactive approach to preparing for future disaster recoveries has helped to ensure that the whole community will be better equipped for subsequent threats and hazards. Santa Clara Pueblo’s recovery experience has also served as a source of inspiration for other tribal nations in the region who face similar fire and flood risks to enhance their emergency management capacities and preparedness frameworks. Pueblo leadership notes that by taking a team approach, any government can leverage their current capacity among functions that support emergency management to collaborate and be successful in disaster recovery and preparation.

Lessons Learned

- The Santa Clara Pueblo embraced continual learning, forward thinking, and innovation to build back better. The tribe’s staff proactively educated themselves on their roles and responsibilities and built internal capacity to fulfill their obligations during and after emergencies.

- A comprehensive understanding of the relationships between the tribe, the state, and the federal government partners involved in the recovery process as described in the NDRF was essential for driving progress on recovery initiatives that helped improve the tribe’s environmental, infrastructure, and economic resilience.

- Proactive collaboration using a team approach among tribal government officials and intergovernmental partners was essential in order for the Santa Clara Pueblo to achieve its restoration and resilience goals.

Case Study Downloads

Santa Clara Pueblo Case Study

Teaching Note: Santa Clara Pueblo Recovery

Additional Resources

- A Tribe’s Collaborative Journey to Develop Forest Resiliency: A Story Map by Santa Clara Pueblo Forestry

- E0210 Recovery from Disaster: Local Community Roles. Check often for upcoming training offerings.

- Santa Clara Pueblo and the Corps of Engineers: A Working Partnership Between Two Nations

- FEMA.gov: Santa Clara Pueblo

- Santa Clara Creek: Headwaters Restoration

- IRC Case Study – Santa Clara Pueblo: Restoring Native Ecosystems to Build Resilience

- Promoting Nature-Based Hazard Mitigation Through FEMA Mitigation Grants.

- Using Engineering with Nature® (EWN®) Principles to Manage Erosion of Watersheds Damaged by Large-scale Wildfires (2021). In Integrated Environmental Assessment and Management (IEAM), DOI: 10.1002/ieam.4453